30 Apr 2013 | Stephen Coan | Original Publication: The Witness

ANYONE

who has visited Argentina, especially its capital, Buenos Aires, will likely

agree with Tony Leon that it is a place where “magic realism is reality”.

Dubbed

the “Paris of the South”, this bustling city sports a sophisticated façade,

reflected in the wide boulevards of the city centre, but edge beyond the sound

of the tango and the smell of coffee, and you find a disconcerting blend of

rich and poor: dilapidated buildings, broken pavements, and ubiquitous

reminders of the country’s chequered past, not least in the kaleidoscope of

races and cultures walking the streets — from the indigenous Indians, decimated

by the Spanish conquerors, to the immigrants of the 20th century.

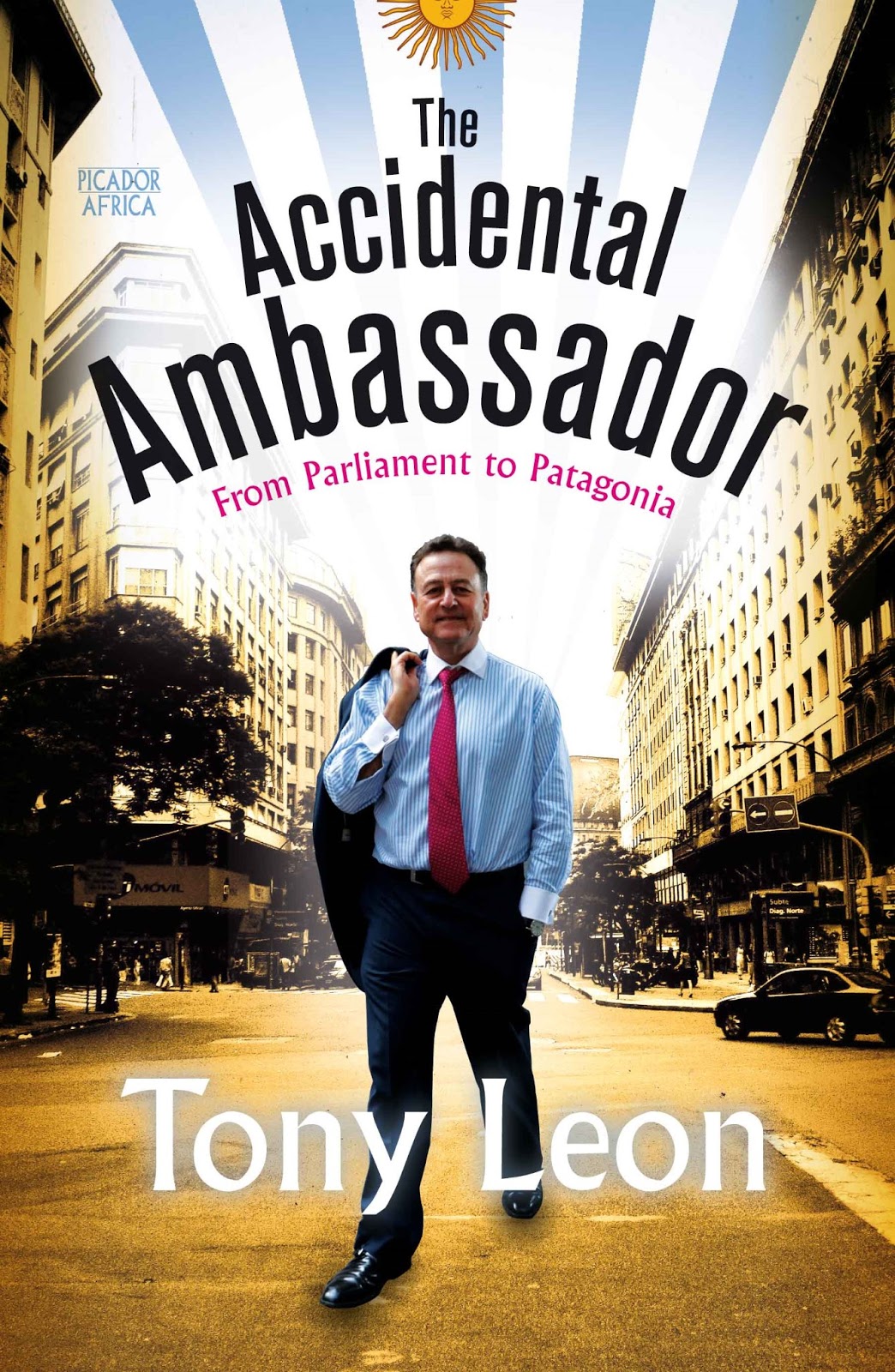

Leon,

former leader of the opposition and head of the Democratic Alliance, enjoyed a

deep immersion in the beguiling melting pot of Buenos Aires, thanks to serving

three years as the South African ambassador and plenipotentiary to Argentina,

Paraguay and Uruguay, now chronicled in his book The Accidental Ambassador.

To

explain the country’s racial jigsaw, Leon quotes its most famous writer, Jorge

Luis Borges, who described Argentina as “an imported country — everyone here is

really from somewhere else”.

The first

half of the 20th century saw a huge immigration of people from Europe

— English, Irish, French, East Europeans and a large proportion of

Italians — who all became part of a boom economy, largely based on beef. An

“emigrant mélange” that is acknowledged in the national joke: an Argentine is

an Italian who speaks Spanish, acts like a Frenchman, but secretly wishes he

were English.

“There is

no escaping the country’s half-baked identity,” says Leon, “thanks in part to

its mainly imported population. And it’s still not come to terms with that.”

Nor has

Argentina comes to terms with its violent past, especially the Dirty War of

1976 to 1983, when a military junta stepped in after a series of quasi

dictators — including the Perons — had plunged the country into chaos. This was

the time of “the disappeared”, a time of torture, state-sponsored killings and

murder — “9 000 was the verified figure, but some estimates suggest nearly

30 000,” says Leon. “It was apartheid on an industrial scale.”

The truth

of much of what happened has never come out. “They never had a Truth and

Reconciliation Commission or its equivalent,” says Leon. “I’m not saying that

everything came out via the TRC, but we made a much better fist of it than the

Argentinians.”

One of

the problems of not having had some sort of TRC process is that nothing was

officially disclosed, says Leon. “So when anyone of note from that period comes

into high office, the question is ‘What did you do in the war?’” says Leon.

As it was

with Pope Francis, who, until his election as pope earlier this year, Leon had

known as the Argentine Cardinal Jorge Bergoglio. “He is a very good man, but

there are questions hanging over him.”

In 2011,

thanks to Bergoglio’s outspoken criticism of Cristina Kirchner’s current

government, Leon found himself and other diplomats flown to the city of

Resistencia in the far northern province of Chaco, to listen to Kirchner’s

address marking the 201st anniversary of the Day of the Revolution, after

having earlier visited the city’s cathedral for a religious service.

“It was

all because Cristina wouldn’t cross the road from the Pink House [the seat of

government] to Bergoglio’s cathedral across the square,” says Leon.

“She

hated Bergoglio because of what he said. When he became pope, she flew to Rome

to bend the knee, but back home she wouldn’t cross the road.”

One topic

that will get Argentines to cross the road together is the Falklands, or the

Malvinas as they are known in Argentina. “It’s something that all Argentines

cross the divide and unite around,” says Leon, as he found to his cost when

hosting a dinner for his Argentine friends and jocularly asked one of them:

“What is it about Malvinas that makes all Argentines so agitated? After all,

you wouldn’t want to go and live on that windswept archipelago?”

The fiery

response saw Leon thereafter determinedly maintain the recommended South

African policy of “strenuous neutrality” on the subject. At least he didn’t add

Borges’ famous comment on the 1982 war between Argentina and Britain as a

“fight between two bald men over a comb”.

Leaving

aside the legacies of the past and questions of identity, the big question is

how Argentina went from boom to bust so quickly. “I was reading an essay by

Marios Llosas Vargas last night, in which he is appalled by Argentina,” says

Leon. “Here was a country ahead of its time, that had a functioning democracy

before Europe. Now it has an economy a quarter that of Brazil and it’s heading

off a cliff.”

Leon was

especially chuffed at having read the essay in the original Spanish, a

language, as he admits in the book, he battles with, as on the occasion he

risked speaking it to welcome 250 Argentine guests visiting the South African

ship Drakensberg: “Good evening and welcome, ladies and horses” — substituting

the word caballos (horses) for the word caballeros (gentlemen).

As is

evident from such stories, The Accidental Ambassador is an entertaining

account of Leon’s three years as ambassador, in a posting that saw the poacher

turn gamekeeper, “representing a government I had resolutely opposed”. One

senses it’s a paradox he never quite resolved.

When an

ambassadorship was first mooted, Leon decided he would only accept a posting

where he would not have to promote policies he did not agree with. “Argentina

was a comfortable fit,” he says. “There were no issues to contend with. It

would have been a different matter if it had been Tel Aviv or Harare.”

Ironically,

it was probably South African foreign policy that played a role in shortening

his stay from four years to three.

“On the

other hand, I didn’t want to watch the clock,” he says. “Also, my wife couldn’t

work, I have an ageing father in Durban, and I felt I had done what I set out

to do.”

What did

he set out to do? Boost trade between the two countries. “There was an 80%

improvement while I was there,” he says. Quite an achievement in a country that

imports as little as possible.

“I looked

for niches,” Leon says. “Argentina is the most protectionist country in the

world; there are no foreign goods. But the pampas came to our rescue. Argentina

is one of the most fertile countries in the world.” And the boom in soybean

production meant there was a need for fertiliser. “We had something they

wanted.”

But when

Leon spoke out on foreign policy — on Syria, Libya and the refusal of the Dalai

Lama’s visa — there was a change of attitude towards him back in Pretoria.

“Whenever I spoke on the phone to them, it was no longer ‘Hello Tony, how are

you?’ but ‘Hello Tony, when are you coming back?’ I waited until the Springboks

came, then I left.”

In 2012,

the Springboks played in the Rugby Championship, the former tri-nations with

Argentina on board, a satisfying coda to the Argentine premiere of the film Invictus,

hosted by the South African embassy shortly after Leon’s arrival in 2009.

Living

far from South Africa, Leon was able to view events here more dispassionately

than he would have in the past.

“But I

would still see things and gasp and gulp. But then, looking at Argentina,

Paraguay and Uruguay, I’d realise we had still got a lot of things right.”

Now Leon

is back, writing a regular column for Business Day, consulting to

potential trade partners and busy on “the paid lecture circuit, as opposed to

the unpaid lecture circuit I was on as a politician”.

Is he

having any second thoughts on his political career, his style of

confrontational politics for example? “Compared to what’s happening now, I

think I was rather an amateur. Now it’s like two parties are going through a

really bad divorce.”

Leon’s

past outspokenness on corruption and growing authoritarianism now looks

prophetic. “I realised what we were up against when the sainted [Nelson]

Mandela made a speech written by [Thabo] Mbeki, in which he said the opposition

is destroying our society.”

“Back

then, there was a strange acquiescence. Perhaps people thought they should give

the benefit of the doubt, but I don’t apologise for what I said.”

Writing

about South Africa in the present, Leon notes the gulf between “the fine

prospectus for a better South Africa, offered by the National Planning

Commission, and the dismal events at Marikana”. For Leon, crossing that gulf

safely and timeously “remains the essential challenge for the future”.

As far as

Leon is concerned, the jury is still out on the National Development Plan. “We

need a Thatcherite determination to take on the unions in this country,” he

says, “to get them on board the NDP because they seem to have declared war on

it.”

But is

the government itself on board? “[Jacob] Zuma told me that the NDP is front and

centre of everything the government does —but he has to make it happen. We need

to see it. In deeds, not words.”

• The

Accidental Ambassador — From Parliament to Patagonia by Tony Leon

.jpg)